Someone (possibly one of my lecturers), once said: ‘People without lists are listless’ – perhaps an observation on my then lack of motivation.

Decades later, I went in search of the origins of this quote and came up empty, although there are many other pithy quotes about the universal ‘to-do’ list.

Author Mary Roach, who has many opinions about lists, says that by making a list of things to be done, she loses “that vague, nagging sense that there are an overwhelming number of things to be done, all of which are on the brink of being forgotten”.

Alan Cohen, author of 24 popular inspirational books says “The only thing more important than your to-do list is your to-be list. The only thing more important than your to-be list is to be”.

I’ve been enslaved to The List since realising, as I tackled university at the ripe old age of 30, that if I wasn’t organised, it would not happen.

I‘d read a few time management books, back in the days when I aspired to be a supermarket manager, but later, embarking upon a three-year Arts degree, I made up my own system. This included hand-written term calendars posted on big sheets of butchers’ paper on the study wall. I had a diary with all lectures, tutorials and assignment deadlines colour-coded and a daily to-do list. The chief instrument of production was a huge old Olympia typewriter I bought from a Toowoomba police office sale. I decorated a large pin board with cartoons and illustrations which had something to say about productivity.

My thoughts on list-making were sharpened on a week-long trek to Gympie’s Heart of Gold film festival, followed by a spot of whale-watching. We have three one-page spreadsheets on which we tick off items every time we pack the caravan for a trip.

For reasons not easily explained, we departed from this time-honoured system and subsequently left home without a dozen items, including bath towels, phone charger, camera charger, SD card (from the camera), video camera (whale-watching, right?), a bottle of olive oil, my favourite pillow, oatmeal soap and a water bottle. Replacing the last two items was a cinch and we bought two towels from a discount department store (wash before using, the label hopefully said). The moral is, if you keep lists, actually look at them.

The three most common types of lists are (1) shopping (2) domestic chores and (3) motivational.

Motivational types will tell you it is not the items on your to-do list that matter, it is the prioritisation. People in general, but mild-mannered, non-assertive people most of all, consistently leave the most urgent and stress-inducing items for last. (Crikey, Mavis, we must talk to Jimmy (16) about his marijuana breath).

Since computers, tablets and smart phones became commonplace in homes and workplaces, the list story has taken precedence. The majority are ‘click bait’, which means whoever invented the list is getting paid for every click that takes you to an ad-festooned page. The worst of these show only one item per page, forcing you to click through if you really want to read about the 10 most successful bandy-legged men.

Some lists are, well, just way over the top. Like the one Franky’s Dad found, a list of the top 34,000 albums of all time. No, M, you don’t have time for this!

Journalist and bloggers have found that the quickest way to write a compulsive article is to turn your topic into a 10-point list. If you write a couple of paragraphs about each item you’ll quickly get to your deadline.

Lists pop up on social media all the time – ten ways to tame a wombat, 25 things you never knew about armpit hair, the top 17 crazy tattoos and so on.

Trivia aside, the shabby state of leadership and lack of sensible policy in this country suggests we all make a short list of important issues about which we feel outraged.

If you come up with more than three major items involving bad policy, prevarication, procrastination or short-term-ism, we need a change of government.

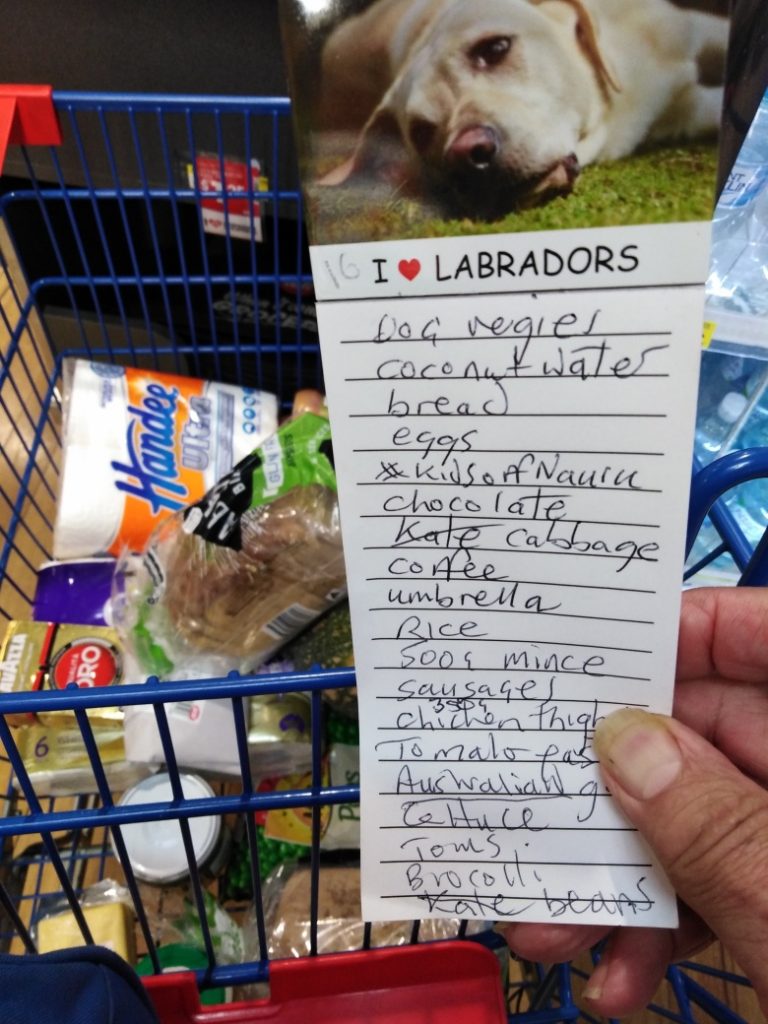

1/ #KidsoffNauru: This has become such a crisis doctors are signing an open letter to the PM; a coalition of humanitarian organisations have given the Federal Government a deadline to get 80 kids (and their parents) off Nauru. About a third of the child refugees left on Nauru are showing signs of Traumatic Withdrawal Syndrome. It is no longer OK to say it is a matter for the Nauruan government and its contractors. Whether these children are brought to Australia by November 20 or not, this has been an appalling outcome of the Federal Government’s refugee policy and should be judged so at the ballot box.

2/ Climate Change: A panel of 91 scientists has definitively told countries what they need to do by mid-century to avert the worst effects of global warming. Our Federal Government’s response to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report (which recommends phasing out coal power by 2050), was predictable. Deputy PM Michael McCormack (who may one day rue uttering these words), claimed that renewable energy could not replace baseload coal power. He said Australia should “absolutely” continue to use and exploit its coal reserves, despite the IPCC’s dire warnings the world has just 12 years to avoid climate change catastrophe. The Guardian quoted Mr McCormack as also saying that the government would not change policy “just because somebody might suggest that some sort of report is the way we need to follow and everything that we should do”.

3/ Homelessness and the cost of housing: You might dimly recall Bob Hawke’s rash promise in 1987 that no Australian child would live in poverty by 1990. Three decades later the goal is as unattainable now as it was then. Even when you take into account that Hawke mis-spoke (the script said no Australian child need live in poverty), it was an empty promise. Nine prime ministers later, close to 731,000 Australian children are living in poverty.

The official homeless figure at the 2016 Census was 116,000, with about 7% (about 8,000 people) said to be ‘sleeping rough’, defined as on the street, on a park bench, under bridges and overpasses, in their cars or in makeshift shelters. These statistics damn all sides of politics, worsening through a period in which there has been no meaningful increase in unemployment benefits or disability pensions.

Meanwhile, property investors continue to borrow money and claim expenses (notably interest payments) against rental income. In 2014-2015, 1.27 million property investors (12% of taxpayers), reduced their personal income tax through negative gearing. No government has yet had the guts to scrap negative gearing or change it in any way.

Economist Greg Jericho analysed a huge Tax Office data dump to glean a few insights – most importantly, 27% of taxpayers claiming on rental properties are in the $80k to $180k tax bracket (and another 8% earn more than that). Furthermore, just over 3% of taxpayers own six or more rental properties. The proportion that own more than one house has been on the increase in recent years.

It’s all too easy to raise other concerns, such as: Adani, Great Barrier Reef, Fracking, the threat to job security for gay teachers and even the Opera House furore (smokescreen that it is).

(Wow, that sure puts my forgetting the towels into perspective. Ed)