In the twilight hours of the Illawarra Folk Festival, the call went out for volunteers. Not those who had already put in the hours to pull off the biggest folk festival in New South Wales. No, this was an urgent call for paying punters staying over on Sunday night to donate 12 hours of their time on Monday for the pack-down. Those volunteering for this task would be rewarded with a full refund of their weekend ticket.

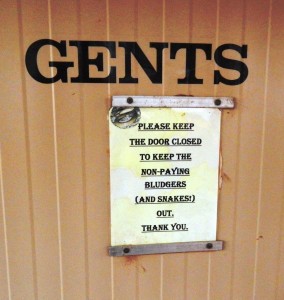

Most of Australia’s music festivals make heavy use of volunteers – (shortened in typical Aussie fashion to “vollies”). The logistics involved in training and managing 2,500 volunteers (Woodford Festival) or 1,300 (The National Folk Festival) is only one side to recruiting a (free) but willing workforce. The fact is there are very few paid positions behind the scenes at music festivals, big or small. Volunteers do the forward planning, the publicity, the volunteer co-ordinating and, once the festival has started, vollies are assigned tasks such as checking wristbands at entrances and exits, managing venues, MC’ing, helping find lost children, looking after artists, spreading straw on muddy patches and the never appreciated but vital task of collecting rubbish and removing it from the site. Volunteers invariably keep the toilets and showers clean and make sure there is plenty of toilet paper. (Except when other people come in behind them and make a mess).

Sometimes being a volunteer at a music festival can be really cool “I got to MC the main stage and actually shook Harry Manx’s hand”. Or “Kate wrote a smiley face on my plaster cast.”

Volunteering has long been a noble task where those who perform work for non-profit organisations and charities do it for no monetary reward, either in cash or kind. Festival volunteers at least get free tickets. In the case of Woodford, a season ticket with camping now costs close to $700, so that is a good inducement to offer one’s services. In return for a ticket, Woodford volunteers are required to put in five hours a day. If you do the math, volunteers are working for about $20 an hour (in kind) over the six-day festival.

That’s a pretty good deal for festival fans whose budgets do not stretch to paying for a full season ticket. (You might be rostered on somewhere else just when Kate Miller-Heidke is playing, but what the hell – she’ll probably write a song about it.)

Firefighters, lifeguards and emergency services

Circling out into the deeper water of volunteering in Australia, I found some statistics which gave me pause to worry about our youth unemployment rate. Close to six million Australians volunteers each put in an average of 135 hours a year. That’s 743 million hours of unpaid labour (per year). It makes you wonder.

Melanie Oppenheimer, chair of history at Flinders University, who has written books about volunteering, said in a 2015 co-authored article in The Conversation that the rate of volunteering has slipped from a 2010 high of 36%. An Australian Bureau of Statistics social survey found that 5.8 million Australians volunteered in 2014 – 31% of people aged 18 or over.

Why is it so?

A panel of academics headed by Flinders University has begun a three-year study to find out why volunteering appears to be in a long-term decline. They hope to find answers to these questions and more:

- Are increasingly busy Australians finding it harder to prioritise volunteering as part of their lives?

- Are we becoming more selfish as a nation and less inclined to help others?

- Is volunteering “on the nose” with young people, the next generation of volunteers?

- Does the decline in volunteering reflect the long, slow decline of rural Australia, where volunteering rates have always outstripped those of their city cousins?

- Has population decline and an ageing population in these areas reduced the supply of willing and able-bodied volunteers?

Adelaide University’s Dr Lisel O’Dwyer has estimated the economic value of volunteering to Australia at $200 billion, using methodology which includes calculating the worth of lives saved by volunteer fire fighters, SES crews and life guards.

But she warned that a focus on the economic value of volunteering can be dangerous, and does not show the whole picture.

Work 70 hours a week for nothing – why not?

Volunteering has come in for a bit of criticism in the past few years, with unpaid internships (sometimes known as ‘work experience’) attracting world-wide opprobrium. Just google “interns and controversy” and you’ll wish you had never started.

There’s also been some media coverage of something dubbed “voluntourism” where predominantly young people can travel abroad and have adventures in exotic locations. The deal is usually food and accommodation in return for a set number of hours working for not-for-profit groups. You can do the legwork yourself, but beware, there are scammers out there all too ready to charge gullible youngsters a fee for finding them an unpaid job overseas.

While volunteers do not get paid for the work they do, local, state and federal governments treat them as part of the workforce. When you volunteer you are covered by workers’ compensation, public liability insurance and the same rules about discrimination and bullying in the workplace apply to volunteers as well.

The biggest exercise in recruiting and training volunteers was in 2000 for the Sydney Olympics, when 45,000 people said “yes” to the concept of being involved in an event that would put Australia on the global stage.

But volunteering is more often about small tasks not even identified as such, like staffing the tuckshop at your children’s school or mending shirts, shorts and skirts for the second-hand uniform shop.

Another star in heaven

Maleny Music Festival director Noel Gardner said even small festivals like the one staged in Maleny last August required 180 volunteers, all of whom were given a free pass in exchange for two shifts of three to four hours over the weekend.

“Festivals couldn’t work without their volunteers,” he said. “The only inducement apart from a free ticket is the joy of helping and perhaps an extra star in heaven.”

Gardner says volunteers often form a family-like bond and friendships are created and cemented year after year.

“I think we (humans) are at our best when we work together for a common cause.”

Friends of ours look after the co-ordinating of volunteers for just one Woodford event (the Fire Event and closing ceremony). Planning for the 120 volunteers needed for this event starts in August, and as our friend said, rarely does a day goes by without something needing to be done.

The upside is that by the time the festival starts, their job is done.

“Obviously we enjoy the tickets to the festival. But we also like the feeling of contributing to a festival we value, and enjoy being part of the organisation and seeing some of the behind-the-scenes planning.”

You, you and you – latrine duty!

Men of my generation probably had fathers like mine (with military experience in World War II). “Never volunteer for anything,” they’d say. Perhaps this is why I have done so little volunteering – car park attendant at the Maleny Wood Expo, MC at Woodford a few times, running a monthly folk club with She Who Only Got Mentioned in the Penultimate Paragraph.

Apart from that, I keep my head down. Evidently there are six million people out there who will do my share for me.