Even though I have lived in the southern hemisphere since I was six years old, Kath Tait’s song about prejudice and xenophobia resonates with me. My folks immigrated to New Zealand, taking up residence in a two-horse North Island town in the 1950s. Kids at our school had strident voices and peculiar accents. I was a novelty – a six-year-old boy with a broad east coast Scottish accent. Women would come into the bakery after school and accost my Mum.

“Make him talk,” they’d say.Not so long after, I lost the accent and started saying fush and chups like all the other fullas. Some 20 years later I went travelling, eventually settling in Australia because it was big and warm, it seemed less insular and there were so many opportunities to live and work in what seemed like different countries within the same continent. So I stayed, got married, had a family and have a piece of paper that says I am Australian, although deep down I’m a citizen of the world and I think we owe it to people fleeing persecution and hardship to offer refuge.

The lure of the land of milk and honey

Mum and Dad were economic refugees in the 1950s. I can remember Mum working out how to make her rations stretch out over a week of feeding two adults and three children – an ounce of butter and one egg per person per week, for example. I remember Uncle giving me the top off a boiled egg like some kind of caviar-like treat. I also remember Dad picking me up from school in a blizzard, pushing his bike through the ever-deepening snow and the gathering gloom.

So what could be so scary about leaving your country of birth and travelling 12,000 miles by sea to the promised land of milk and honey? It was probably the first and only time my Dad had a six-week holiday where his every need was taken care of, from the quiet knock on our shared cabin door at 7am (cup of tea Mr Wilson?), to the leisurely three-course dinners in the tourist-class dining room. Of course the Promised Land was not quite what they envisaged and the sponsoring employer didn’t do the right thing, but they persevered, making a good impression, going to the Kirk on the Sabbath and spending the afternoon listening to Jimmy Shand records.

Whatever happened to the open door?

New Zealanders and Australians have a bit of a hide taking the piss out of strangers and foreigners when one in four of us were born somewhere else. And now we have a government which is skating as close to a White Australia policy as you could possibly get. True, Labor governments have ballsed up our refugee/asylum seeker policy too. But it’s not that hard, as Kath Tait says in “Strangers and Foreigners.”

Lots of people think, when they own their own homes,

That they can keep the immigrants out of their living zones.

Strangers and foreigners are everywhere

But they don’t bother me, no I don’t care.

If you look at yourself you just might find

A stranger or a foreigner in your own mind.

So be kind to yourself and have some care

For strangers and foreigners everywhere.

Kath’s song goes on to discuss gays and lesbians, fools and dickheads and generally preaches tolerance in her uniquely under-stated way. We could do with more Tait-isms in this country. Our policy of diverting refugees and asylum seekers to offshore detention centres is not in any way defensible. It seems such a reversal of our acceptance of British and European migrants in the 1950s and 1960s and the Vietnamese in the 1970s. My folks looked forward most, I’m told, to an egalitarian land where anyone could “have a go.”

Second class wait here

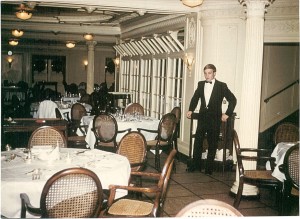

My elder sister tells a story about the day we boarded the Rangitiki at Tilbury near London in 1955. She was 14 at the time so remembers clearly a voice over the ship’s loudspeakers: “Mr Robert Wilson, telegrams for Mr Wilson can be collected at the Purser’s office.” So my sister was sent to collect the telegrams. But she got lost and ended up in the first-class dining room where a waiter who was setting out the silverware for dinner kindly gave her directions.

“Have a good look around,” he apparently said. “Because once we sail you won’t be allowed up here.”

We sailed to New Zealand, via Curacao, The Galapagos, the Panama Canal and Pitcairn Island. I was at first confined to the nursery with younger children and babies until I complained loudly and often until I was released into my father’s custody.

So the five of us, from somewhere else, settled in New Zealand and Australia and now there are 30 whanau or extended family.

I’ve written a couple of songs about this. Impressions of New Zealand is just that, based on letters my Mum wrote about our first year in the colonies. The companion piece, Rangitiki, is more about emigration, economic refugees and why it was OK then but it is not OK now.

Now there’s a YouTube video, out there for anyone who wants to watch and listen and catch the subtlety of the message. I’m indebted to the photographers who allowed me to use their images, particularly Lukas Schrank, who has produced a 15-minute animated documentary about Manus Island, in which two detainees tell their stories over the telephone. We supported this venture when Lukas raised money through Pozible for post-production. Some of the stills from this movie appear in our video.

Seven million and counting

Not everyone will agree with my take on emigration and refugees and that’s OK – it’s a free country. I consider myself to have ‘small l’ liberal ideas in the true sense, that all persons should be treated equally. I have a big problem with the Australian Government spending our tax dollars to keep people in onshore and offshore detention centres without those people being charged or convicted of an offence. Seven million people have come to these fair shores since World War II and made a life for themselves and their families. It is fundamentally unfair not to extend the hand of friendship to those who arrive here by unorthodox means, driven by persecution, fear and desperation.

As former PM Julia Gillard told the Migration Council conference in 2013.

“We are a nation of migrants. I know – because I’m one myself. My family made that journey of hope and courage to a new land.

Together we have built a nation that strives to be classless, confident and compassionate. But above all, a country which is decent. A country that has been enriched by the hand of welcome each generation holds out to those who come after us.”

I followed 13 years later on the Aranda – but to a ‘good’ job as a scientist in the erstwhile DSIR in Nelson. bigotry – yes some for a short time until they found that they could not fit you to a stereotype. Others saved every penny to go back to UK… and came back 6 months later with tail between legs – they forgot why they left in the first place. Pay was poor – a policemen earned more when they started at plod school – but 2 h tomato picking from 0500 helped the books to balance. And the sun did shine.

Thank you! Another thought-provoking piece, XXXX