Life’s most embarrassing moments. It is sometime in 1996 and I am attending a corporate function as a business reporter for The Courier-Mail. I am about as excited as I get, because for the first time I have the prospect of meeting the great Gough Whitlam. He has been invited to the conference to engage in a debate with Sir James Killen. Firebrands of the left and right; true intellectual discourse, brimful of wit and rhetoric and demonstrating a transparent fondness for one another.

Life’s most embarrassing moments. It is sometime in 1996 and I am attending a corporate function as a business reporter for The Courier-Mail. I am about as excited as I get, because for the first time I have the prospect of meeting the great Gough Whitlam. He has been invited to the conference to engage in a debate with Sir James Killen. Firebrands of the left and right; true intellectual discourse, brimful of wit and rhetoric and demonstrating a transparent fondness for one another.

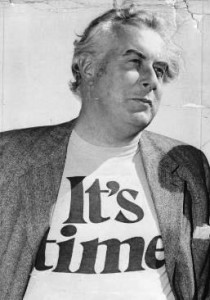

I spot the man in the lunch break standing by himself near a platter of fruit, cheese and crackers. I approach, shake his hand and offer my business card. I look up (Gough was very tall), as he inspects the card.

“Oh, The Courier-Mail!” (an orator’s voice, laced with gathering opprobrium). “That’s what’shisname, that crank who keeps going on about Manning Clark.” And with that he turned and walked away.

He was referring to a series of articles in The Courier-Mail in 1996 that claimed the late historian Manning Clark was an “agent of influence” of the Soviet Union. I returned to work that day and confided the story to a few of my colleagues. We agreed it indicated a degree of haughty arrogance, but given the long friendship between Gough and Manning Clark, it was an understandable reaction. Crikey, I didn’t want an interview, I just wanted to shake his hand.

The series of articles mentioned above caused a great fuss at the time. Later that year, the Press Council upheld a complaint by 15 prominent Australians, saying the newspaper had insufficient evidence to claim Professor Clark was an agent of the Soviet Union or that he was awarded the Order of Lenin. But, as is the case with all daily newspapers, the content has long been forgotten, the paper recycled as garbage wrap or garden mulch.

That’s the problem when great men or women die – their lives get picked over by journalists, each as keen as the next to find that little untold vignette. I was not even in Australia when Gough was sacked in 1975 by the then Governor-General John Kerr.

I remember reading coverage in the UK newspapers and wondering if there would be a revolution in Australia as a result. Gough would probably find it amusing that his passing alone was the news event that pushed Tony Abbott off social media. Most of the FB tributes to Gough were touching, some even overly-emotional. I posted a link to the Whitlam Institute and a summary of the Whitlam Government’s achievements. It is almost 40 years ago, so for those not even born then, here’s a summary:

“The Whitlam Government brought about a vast range of reforms in the 1071 days it held office between December 5, 1972 and November 11, 1975. In its first year alone, it passed 203 bills – more legislation than any other federal government had passed in a single year.”

Under Whitlam, women trapped in loveless, abusive marriages were able to escape and apply for the Supporting Mothers’ Pension (or men for the lesser known Lone Parent Pension). Pregnant women without a partner were able to keep their babies instead of adopting them out. Under Whitlam, bright children from poor families were given a free university education (this continued until HECs was introduced in 1989).

Medibank, Medicare and Medibank Private

In 1974, Whitlam created Medibank, a national health insurance system providing free access to hospitals and other medical services. Medibank (re-named ‘Medicare’ in 1984) provided health coverage for the 17% of Australians who then could not afford private insurance. A year later, Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser introduced the government- owned Medibank Private, with the aim of providing competition in the insurance sector.

Labor governments opposed any notion of Medibank Private being sold/privatised/floated, just as Liberal politicians, starting with John Howard, swore that if elected they would sell off Medibank Private.

Medibank was a national public authority until PM John Howard made legal and accounting changes in 1997.

These changes made it easier for Tony Abbott to appoint agents of private enterprise as Joint Lead Managers (ie float promoters) to run a public float. The heavy irony is that the prospectus for Medibank Private, which is going public this year, emerged the day before Gough passed on.

It is an expensive business. If you delve into the 204-page prospectus you will find that $17.5 million has already been set aside for fees paid to accountants, auditors, lawyers and business and capital market advisors. The float promoters, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs and Macquarie Bank, will collect a $5 million fee and up to $5 million in incentive management fees if the float goes well (plus commissions).

You will hear a lot about Medibank Private now that the prospectus is out and about. A 2012 Harvard University survey found that two-thirds of investors do not read a prospectus before applying for shares. They rely on people like me, sifting out a few key points.

• There is a restriction on any one shareholder (or its nominees) holding more than 15% of Medibank Private. This ensures that a predator cannot build a 20% stake, which triggers a takeover;

• Unhappily for some, this provision will lapse after five years;

• The government is selling 100% of Medibank Private – in previous privatisations the government has usually kept an interest;

• The nominal share price is between $1.55 and $2.00; but you have to send your cheque before you find out the final price;

• The dividend yield of between 4.2% and 5.2% is not generous. Retail punters and SMSFs could leave their $20,000 in a fixed term deposit at 3.5% without any risk at all;

• Medibank’s four million policyholders will be able to buy more shares, and earlier, but otherwise derive no bonus from the float.

There is a lot more in this document as the promoters cover all the bases by making sure you know about the risks and the competitive pressures in the health insurance business. The Abbott government says it will spend the proceeds of the float (up to $5.5 billion), on its Asset Recycling Initiative, providing payments to States and Territories that sell assets

and re-invest in Australian infrastructure.

I am aware there are people out there who think Medibank Private should remain a government asset. In 2013 it paid the government a dividend of $450 million, so it’s a handy investment.

There are also people who say all health care should be free. Or at the very least, a poor person needing elective surgery should not have to wait two or three years when those with private insurance can have it done next week.

In his 1972 election campaign speech, Whitlam outlined his reasons for introducing universal health insurance.

“I personally find quite unacceptable a system (ie in which private medical insurance was tax deductible) whereby the man who drives my Commonwealth car in Sydney pays twice as much for the same family (medical insurance) cover as I have, not despite the fact that my income is 4 or 5 times higher than his, but precisely because of my higher income.”

Hear, hear, Sir.

Good one Bob. Ironic that the wheel has turned – full privatisation of medical insurance at the time that Whitlam died. It is amazing how much his Government implemented in a little over 1000 days, in terms of fundamental social reform – does that make the current Government’s floundering efforts social deform?